The following is an excerpt from: (2012) M.R. Harrington and the Lost Mound in Hempstead County, Arkansas. Caddo Archeology Journal 22:63-76.

This is a story about a discovery. This is a story offering clarification. This is a story that generates additional questions and provides tantalizing leads to pursue additional research. This is a story about a mound site that no longer exists. A mound site where an interesting artifact – a lizard-like bone effigy pendant – was discovered in 1916 at the confluence of the Red and Little Rivers in Hempstead County, Arkansas.

The man who visited this now long-gone mound site and found this curious artifact was Mark R. Harrington, at that time an archaeologist with the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation. He came to southwest Arkansas to continue exploring the Red River north and west of Fulton, Arkansas and pick-up where Clarence B. Moore had ended his Red River explorations, five years earlier.

It’s surprising that Harrington even attempted to visit this Hempstead County mound site, what he calls both the Mound on Battle Place and the Battle Farm, noting that upon arrival in Fulton his group of explorers found “that the Red river was at high flood stage, in fact, breaking through the levees into the village of Fulton as we arrived, and that the lowland, where lay many of the mounds we had hoped to explore, were completely under water and inaccessible.” They ultimately decided to make a change of plans and move their explorations northward away from the flooding toward the Ozan Creek drainage, an area where much of the work he conducted is frequently referenced in Caddo research.

But before he and his crew headed north, they “learned that there was a mound on the Battle Farm, some three miles west, which remained out of water and could be worked without trouble, a mound that had yielded a pottery vessel to the desultory scratching of local collectors.” In the interest of reducing confusion, I will refer to this site as Harrington’s Battle Mound.

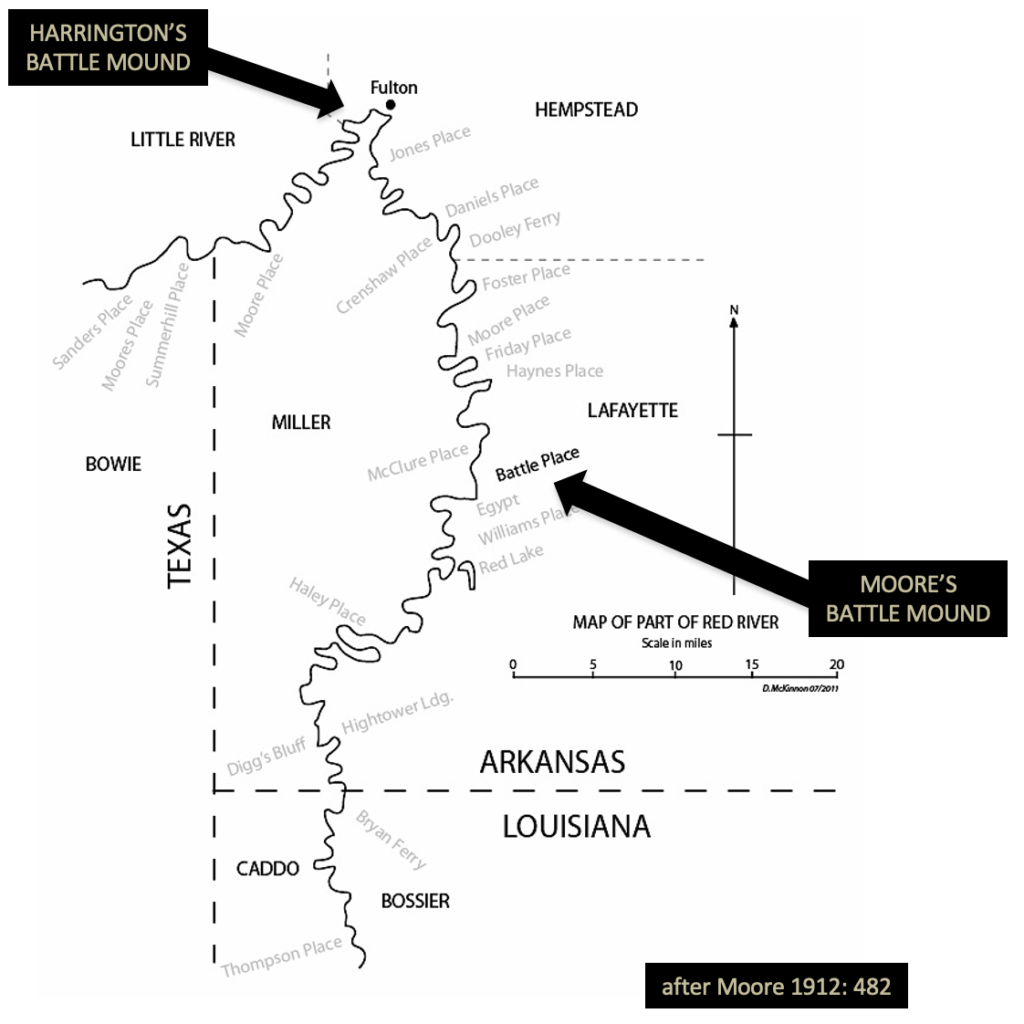

I mentioned this story offers clarification. In fact, there are TWO Battle Mound sites. One recorded by Mark R. Harrington, as I have already mentioned, and the well-known mound site recorded by Clarence Moore in 1911. Moore’s Battle Mound is located in Lafayette County, some 37 kilometers as the crow files or about 75 kilometers following the current meandering channel of the Red River and south of Harrington’s Battle Mound. The state trinomial for the Lafayette County Battle Mound is 3LA1 and I will refer to this site as Moore’s Battle Mound.

Moore’s Battle Mound is frequently cited throughout Caddo literature as Battle Mound or the Battle Place. The site contains a large multilevel platform mound that looms over the current landscape. The large mound is composed of at least three platform levels oriented south to north and a large slope on the eastern side of the mound. It measures 200 m in length by 90 m in width. Many Caddo vessels have been excavated from the site throughout the 1920s, 30s and 40s, allowing subsequent researchers to consider an occupational span of at least AD 1200 to AD 1600, if not earlier.

So, a seemingly obvious question is, “Why do these two sites, located some distance apart from each other, share the same Battle name?”

James J. Battle, born in North Carolina, slowly moved his way westward through Mississippi and into Arkansas in the 1840s. By the 1850s, he is listed on the tax rolls as the owner of the entire quarter section where Moore’s Battle Mound stands today in Lafayette County. One of Mr. Battle’s sons, N. O. Battle or Napoleon O. Battle, is shown as living in Nevada County on the 1880 census rolls with a son, Joseph J. Battle, listed at eight years of age. By 1914, Joseph J. Battle, grandson of James J. Battle and a Fulton merchant and landowner, purchased several plots of land east of Fulton including the land containing Harrington’s Battle Mound. Joseph Battle died in 1930 under strange circumstances, falling off a boat and drowning.

The mound that Harrington recorded was a platform mound, like the large mound at Moore’s Battle Mound in Lafayette County. However, the mound at Harrington’s site is much smaller. The dimensions are 25 m by 14 m and only a couple meters in height. The longest side of the mound is oriented east to west with the possibility of multiple platforms from conjoined mounds. Harrington continues, “The middle portion was only three or four feet high, but there seems to have been a small mound at each end of the platform, for at these points the structure, even in its present dilapidated condition, is two or three feet higher”.

Harrington and his crew spent several days working at and around the mound at the Battle farm with little success beyond “village refuse, and one specimen from the general digging that was really unusual – [a] lizard-shaped bone awl or pin” and “appears to be a lizard effigy”. It is this unusual pendant that initially spurred my interest in identifying pendants at other sites and their distribution across the landscape. In doing so, I quickly realized that Harrington’s Battle Mound is not the same as Moore’s Battle Mound. In other words, the pendant Harrington found did not come from Moore’s Battle Mound – 3LA1 in Lafayette County – as so many researchers have incorrectly stated.

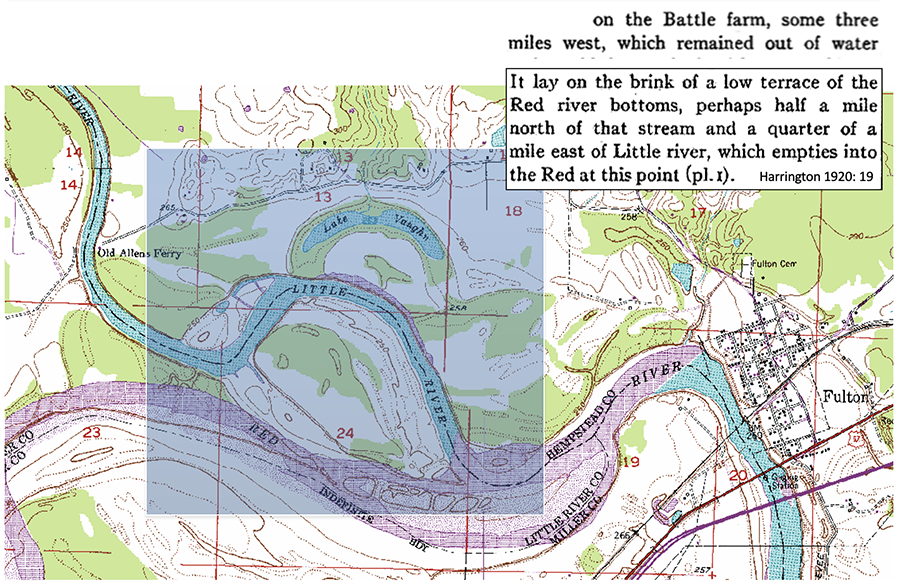

Harrington describes the site as located “on the brink of a low terrace of the Red river bottoms, perhaps half a mile north of that stream and a quarter of a mile east of Little river, which empties into the Red at this point”. Using Harrington’s directions, which include the words “some” and “perhaps”, implying his measurements are estimates, the area of interest is roughly within the shaded box below.

Clearly the dynamic nature of the Red and Little River prohibits the use of contemporary maps to try and make sense of Harrington’s directions. After all, it’s been 100 years since he visited the site. This is where the use of historical maps is crucial – in particular a U.S. Department of Agriculture 1916 soil survey map. I’ve cropped the map to the area of interest with the confluence of the Little and Red Rivers in the NE corner of Section 23. Fulton is to the east, situated where the Red River turns to the south, also known as the Great Bend. The map contains township, range and section boundaries that can be georeferenced and compared to current spatial datasets.

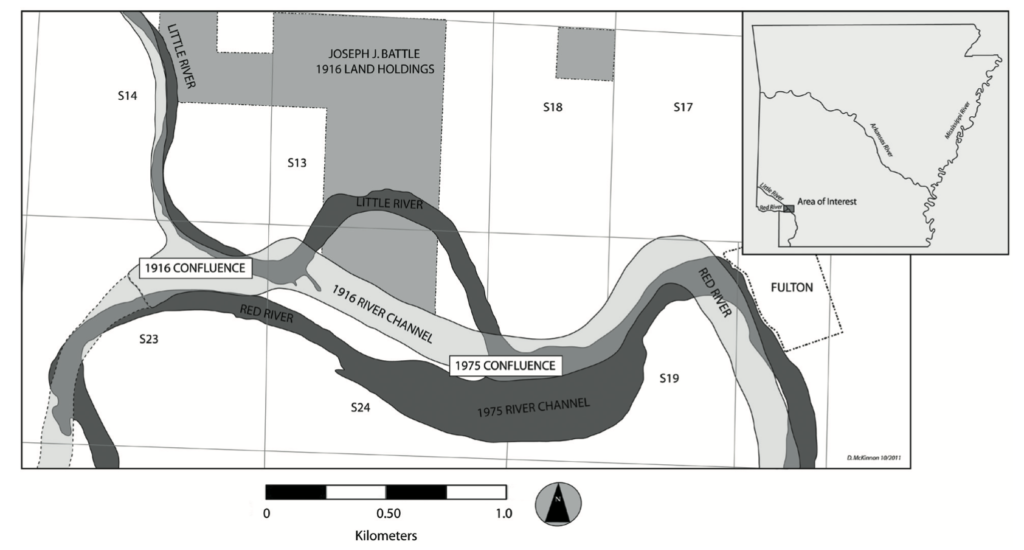

When compared and overlaid onto the photo revised 1975 USGS Quadrangle map, there are significant changes, not only the course of the river, but the location of the confluence. In 1916, the confluence was in Section 23 and in 1975 the confluence had moved almost 2.5 kilometers east toward the town of Fulton. Since Harrington mentions the confluence of the Little and Red in his description, this information is necessary in hopes of identifying the location of the mound he explored. Also necessary is an understanding of where the Battle Farm existed at this time.

With a better understanding of the 1916 landscape, the broad area of interest can be narrowed by looking at the property that the Joseph Battle owned at the time of Harrington’s visit. According to the 1914 Hempstead County tax rolls, Joseph Battle acquired tracks of land in Sections 13, 14, and 24 of Township 13 South, Range 27 West and Section 18 in Township 13 South, Range 26 West. In Section 24, his holdings are listed as the “Fractional all 79.61 acres”, since the southern portion of his holdings bordered the northern bank of the Red River at that time.

Now, using the 1916 Battle holdings as the spatial framework, I examined all the known archaeological sites that fall within those boundaries – none are recorded as having a mound. But, that is not unexpected considering that Harrington recorded the mound site as being in a “dilapidated condition” in 1916. Not to mention the site having been victim to the agricultural plow over the subsequent many years, as well as the meandering river.

It’s impossible to determine at this stage, which, if any, of the known sites correspond to the site Harrington visited in 1916. Nonetheless, in this area Caddo ceramics have been identified on what was Joseph Battle’s property. Clearly, the mound is gone or indiscernible today. However, could archaeological material related to the mound be buried beneath river deposition? Based on recent CRM surveys that indicate a potential of a buried sub-plowzone site and the artifacts that were recorded, I think so.

So, in closing this story, I have provided clarification. Harrington’s Battle Mound is not Moore’s Battle Mound. I have offered leads to pursue additional research. And lastly, I have proposed a sad fact – the mound at Harrington’s site likely longer exists on the landscape. But the story doesn’t end with that fact. Using historical maps to reconstruct the 1916 landscape it can be realized that a lost mound did exist in the area where the Little and Red Rivers come together and, interestingly… perhaps importantly, is where an curious artifact – a lizard-like bone effigy pendant – was discovered by Mark R. Harrington in 1916 in Hempstead County, Arkansas.

For more information:

| Bohannon, Charles F. 1962 Excavations at the Mineral Springs Site, Howard County, Oklahoma. The Arkansas Archeologist 3(10):7-9. Harrington, Mark R. 1920 Certain Caddo Sites in Arkansas. Indian Notes and Monographs, Miscellaneous Series No. 10. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York. Hoffman, Michael P. 1971 A Partial Archaeological Sequence from the Little River Region, Arkansas. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, Cambridge. McKinnon, Duncan P. 2017 The Battle Mound Landscape: Exploring Space, Place, and History of a Red River Caddo Community in Southwest Arkansas. Research Series No. 68, Arkansas Archeological Survey, Fayetteville. Moore, Clarence B. 1912 Some Aboriginal Sites on the Red River. Journal of Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 14:481-638. |