The following is an excerpt from: (2015) Zoomorphic Effigy Pendants: An Examination of Style, Medium, and Distribution in the Caddo Homeland. Southeastern Archaeology 34(2):116-135.

A few years ago, late one evening, I found myself turning the pages of the well-known Mark Harrington manuscript from 1920, entitled “Certain Caddo Sites in Arkansas”. At that time, I was attempting to identify any hidden details that Harrington might have recorded about the Battle Mound site. It wasn’t the first time I had read Harrington’s manuscript, especially his descriptions of what he calls the Mound on Battle Place. It was, however, the first time I noticed that the Battle Mound he discusses is in Hempstead County and is not the same site as the large multi-platform Battle Mound in Lafayette County, a discussion I presented at the Arkansas Archeological Society annual meeting and write about in the most recent Caddo Archeology Journal.

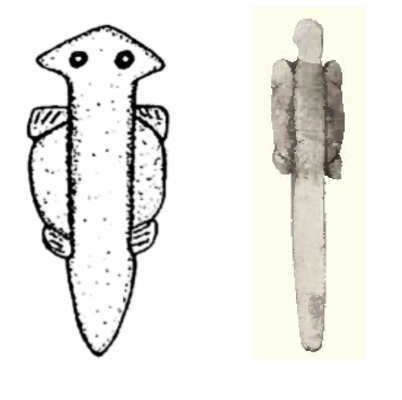

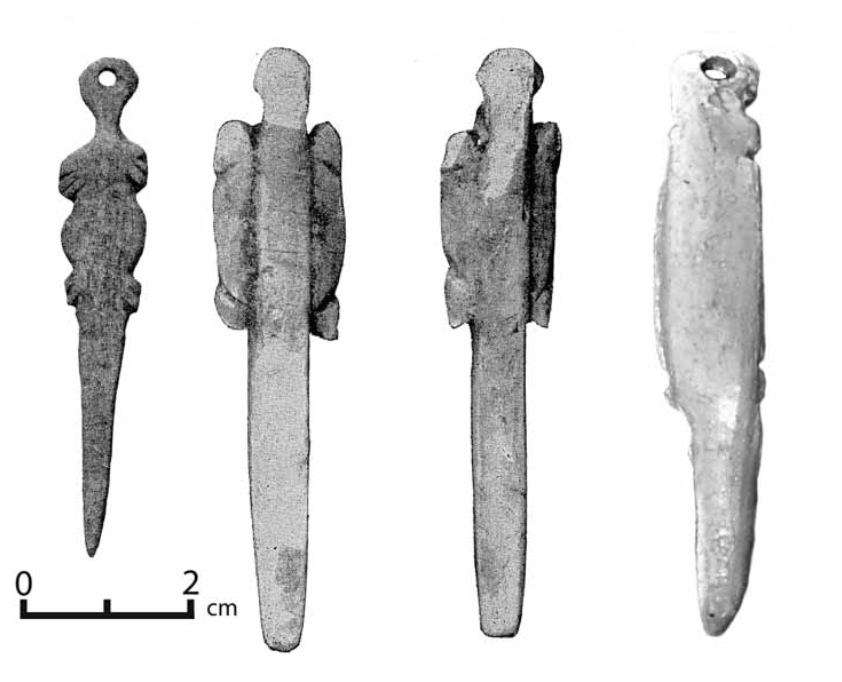

At the Hempstead County Battle Place Mound, Harrington and his crew spent several days testing and found what he describes as general village refuse and one specimen from the general digging that was “really unusual – a lizard-shaped bone awl or pin that appears to be a lizard effigy”. The effigy pendant he illustrates was the impetus that sparked my curiosity in not only identifying other pendant examples toward a comprehensive corpus, but to also investigate attributes of this interesting object as they relate to style, form, and distribution.

I have been able to identify 124 examples of decorated and undecorated effigy pendants documented in various literature sources from 14 known sites throughout Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma. These sites are located along the Red River in northeast Texas, southwest Arkansas and northeast Louisiana, along the Black Bayou, Big Cypress, and upper Sabine River basins in northeast Texas, on the Ouachita and Arkansas Rivers in more or less central Arkansas, and a single pendant from Spiro along the Arkansas River in Oklahoma. Most of the pendants come from contemporaneous Belcher phase components at sites along the Red River and from Titus phase components at sites in northeast Texas.

STYLE BACKGROUND

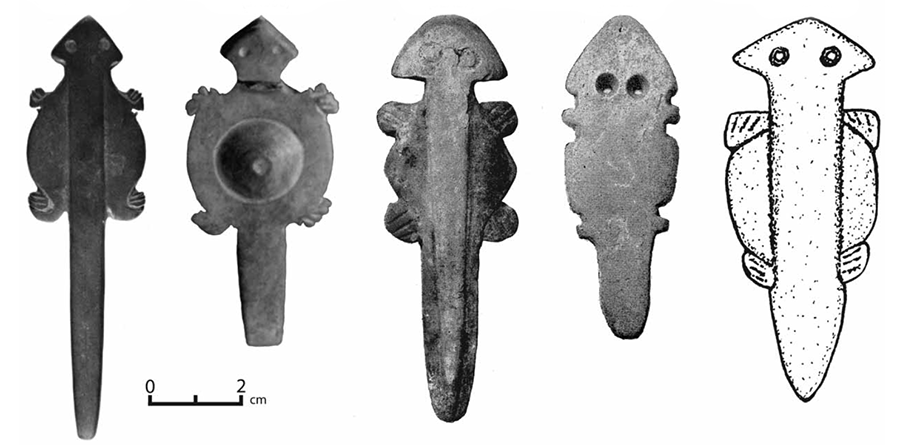

Some initial investigations related to the style of these pendants have been undertaken. Clarence Webb, in his Belcher manuscript, is the first to propose two stylistic categories. What he calls Group 1, is “an animal with wider body, definite feet with toe markings, eye markings or perforations, but without parallelogram-and-dot engravings.” He suggests that superficially, Group 1 look more like amphibians, such as “lizards, salamanders, or even alligators” with “blunt tails, stubby legs with broad feet, and broad, triangular head [that] are more suggestive of salamanders”.

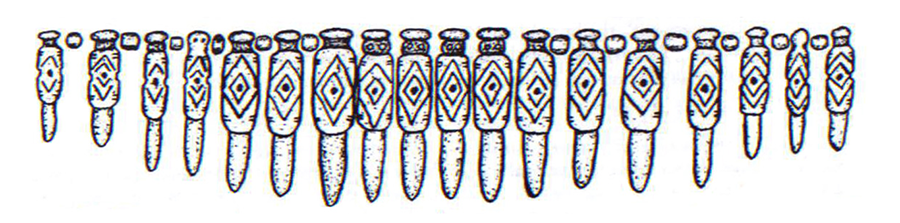

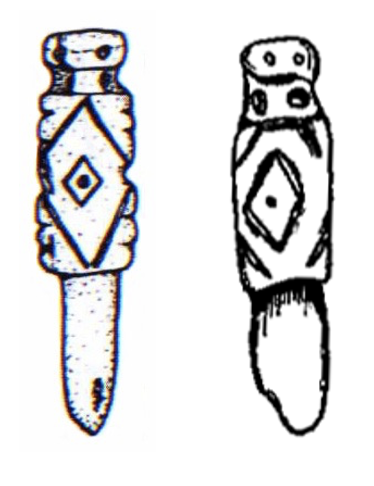

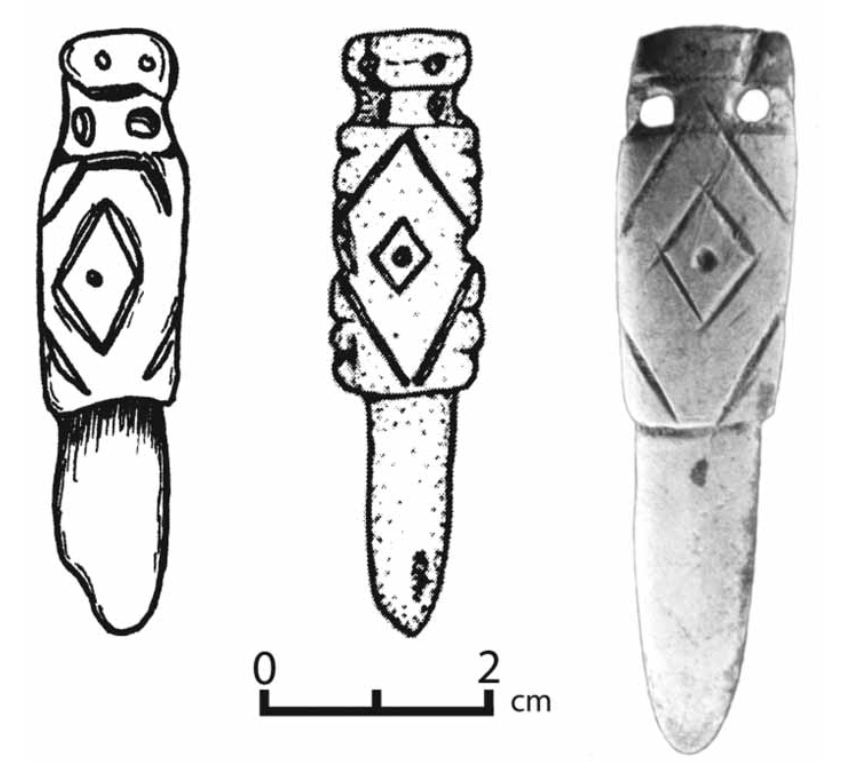

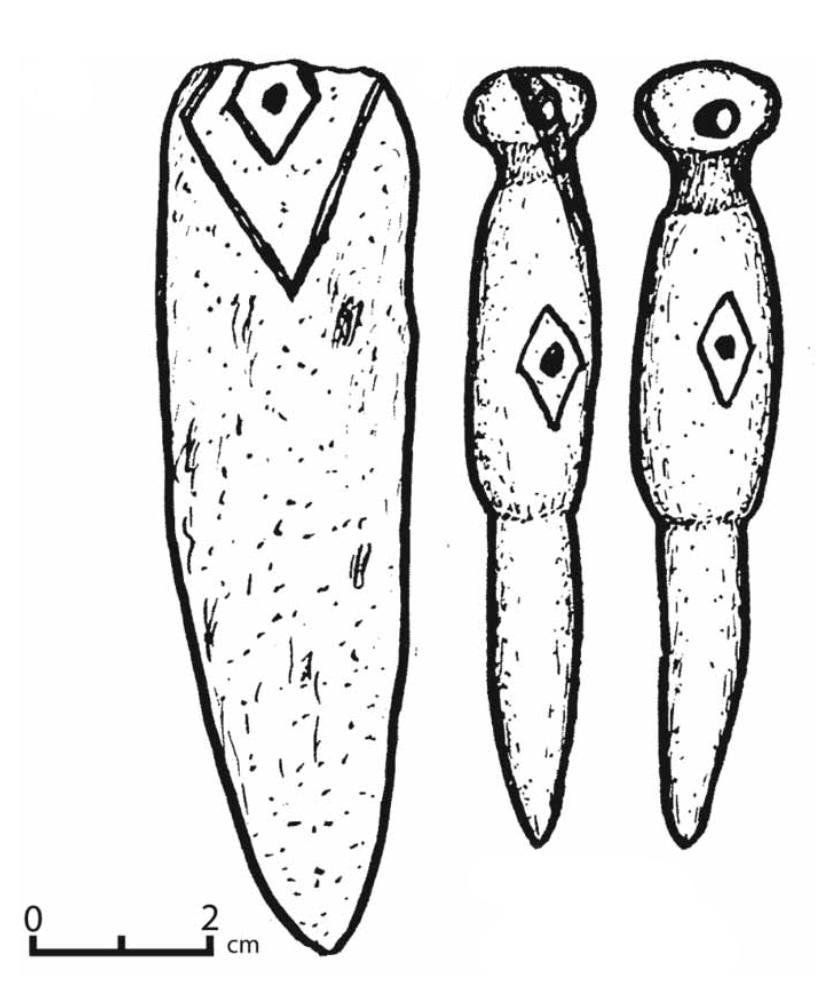

The second group, what Webb calls Group 2, is “the long, slender pendants cut from conch columella or thick conch wall, having only side notching as extremity representations, a well-defined neck segment which is usually perforated, eye representations in some instances, almost always bearing the double parallelogram-and-dot markings on the body segment, and usually having rounded, flat-topped heads.”

Recent research by Elsbeth Dowd on amphibian and reptilian imagery in Caddo art includes a discussion and further elaboration on pendant style and classification. The first group, what Webb refers to as Group 1 and Dowd identifies as Group A, include “pendants in which four feet are clearly discernable, either in plan view or through engraved tow markings” and with a “triangle rather than a rounded head”. The second group, what Webb refers to as Group 2 and Dowd identifies as Group B, are pendants with rounded heads and body markings of “an engraved dot within a diamond [at the] center of each body, which is almost always enclosed within an additional engraved diamond.” Some of the Group B pendants might have stylized feet that have been “notched on the sides of the body in the same location where feet were indicated in Group A”.

Using the framework established by Webb and Dowd, I propose a further refinement of the classifications of these pendants. I first review and classify by style (keeping the letter designations used by Dowd), then examine form, mostly in terms of the artistic medium, and last offer an analysis of the distribution of the pendants across the Caddo Area, which possibly suggest underlying spatial-cultural rules or traditions.

STYLE

Group A

Group A1 is based on the primary definition already established by Webb and Dowd. They have a wider body, discernable feet, triangular heads, two eye markings or perforations, and with only minor engravings, mostly as notches that likely represent stylized feet. In terms of depictions, they are more salamander-like in form with the stubby legs with broad feet and a broad, triangular head. There are nine pendants in this subgroup.

The two minor deviations from this pattern are the two outlined in red. One of these is likely a profile representation and contains and angled line, which could be related to natural inclusions in the shell. The second is more avian-like, with no discernable feet or eye markings, or perforations.

Group A2 is designated primarily based on a more slender design rather than the wider pendants in Group A1. Additionally, the pendants in this subgroup contain a more rounded head, with a single eye perforation, as opposed to the more triangular head in Group A1. There are six pendants in this subgroup. The two illustrated pendants from the Foster site do not look to contain eye perforations, but it is difficult to discern if an eye marking or design is present on the head. In terms of depictions, they are more grasshopper or locust-like, as has been suggested elsewhere in the literature.

Group B

Group B1 is based on the primary definition already established by Webb and Dowd. Of the entire pendant corpus, Group B1 is the most represented, with 86 pendants total – 56 of them from Belcher and 18 from Clements. Attributes are slender pendants with an engraved pattern of a two parallelograms or diamonds (depending on how one holds the pendant), usually with a dot in the center. The upper portion, or “head”, is typically rounded with perforations or “eyes” just below. An image of a single pendant from C.T. Coley in northeast Texas has yet to be found, but has been described as virtually identical to others within this group. In terms of depictions, they have been suggested to represent cicada, with the possibility of the concentric diamond element representing folded the wings resting on the body.

Group B2 contains a total of 10 pendants. At the Belcher site, two pendants were found together as part of a necklace. The Belcher pendants are similar in that they contain a single diamond with central dot and lack any notching that might represent legs. A third pendant from the Belcher site is dissimilar in form but contains the concentric diamond-with-dot motif. The varied use of the diamond motif might suggest an underlying application of Pars pro toto, or Part taken of the Whole, where parts or portions of a design motif still serve to imply meaning within a larger and familiar set of cultural narratives and ideology.

|  |  |

FORM

Shell

In terms of material used or form, shell is the most dominant. Seventy are documented as being made from the split collumela of a marine conch shell – the majority of which contain the diamond-with-dot motif. They range in size from 3.7 cm – 15.2 cm in length and 1.1 cm to 1.4 cm wide.

Forty-seven are documented as being carved from the thick outer wall of a marine conch shell. They range in size from 4.4 cm to 10.1 cm in length and 1.2 cm to 4.1 cm wide. The Group A salamander-like style and Group B cicada-like styles are both represented with the shell wall material or form. There are two examples of the use of mussel shell. The use of marine conch shell, an exotic resource from the Gulf Coast some distance away, suggests an importance as an artistic medium imbued with socially restricted access or use.

Stone and Bone

Other less utilized mediums include stone, such as green slate, and limestone or soapstone. A single bone pendant was found at the Battle farm site in Hempstead County, documented by M.R. Harrington in 1920.

DISTRIBUTION

In considering the distribution of pendants across space, a north-south heterogeneity in style and form is apparent. Sites in the Red River region and the three sites along the Black Bayou, Big Cypress, and Upper Sabine Basins in northeast Texas contain a majority of pendants that fall into Group B shell pendants – that is they most resemble the cicada-like style constructed from either the columella or wall of a marine conch shell.

Those sites north contain more Group A style category than Group B with a greater diversity of mediums or material used – that is they most resemble the salamander or grasshopper style constructed from soft stone or bone.

So, what does all this mean as it relates to possible underlying spatial-cultural rules or traditions associated with the creation of these intricate and fabulously crafted pendants? Using the established framework of zoomorphic style, form, and distributional attributes, some initial insights can be offered regarding the manifestation of social, political and economical behaviors.

For example, style can be thought of in terms of a social cohesion expressed across space and time as “an indicator of a reconstructed period of time when a single idea, a very complicated specific idea, was being put into material form.” Might the north-south delineation between grasshopper-like and cicada-like effigy representations suggest the presence of a single complex idea containing regional manifestations? That is, an idea associated with larger symbolic narratives regarding the transformative nature of grasshoppers or cicadas that has differentially been put into material form across disparate geo-cultural areas?

In terms of political behaviors, the overall rarity of pendants (those known about, of course) across such a large area hints at the importance of their social value. The marine conch shell and the exquisite necklaces they constitute were originally sourced from the Gulf Coast, some distance away. Access to a limited resource suggests that the pendants were imbued with political importance as “powerful symbols worn by the social elite that had access to exotic marine shell raw materials or goods” and certainly demonstrative of a social hierarchy tied with differential access to a prized cultural and political resource. It is interesting to note that of the pendants found at sites along the southern Red River are all constructed from marine conch shell. This, along with the overwhelming presence of the similarities of effigy pendants at the Belcher site (particularly those associated with style Group B) leads one to further consider the Belcher site as political and ideological center of esoteric information, complete with the political and priestly retainers of this symbolic narrative. In other words, could the diamond-with-dot motif, so prominent at Belcher, represent a geographic identifier, a badge if you will, of an important political and ceremonial location?

Lastly, certain economic behaviors can be inferred from the distribution. Foremost is the suggested interaction and likely trade between the Belcher and the Clements sites – a site containing 18 pendants that are identical to those found at Belcher. Archaeological evidence suggests that the pendants at the Clements site were not made locally but were “obtained in trade with other aboriginal groups, especially those that had ready access to marine shells from the Gulf Coast”. This trade suggests not only economic interactions between these two locales but the possibility of a shared inter-regional narrative tied to these objects.

Independently, the spatial distribution presented here offers only inferences to be further explored. Moving forward, the inclusion of additional spatial-cultural data sets or layers, most notably ceramic distribution as I’ve explored elsewhere, can provide complementary and related variables toward a more refined delineation of centers of social, political and economic influence as expressed and validated through the style, form, and distribution of finely crafted and socially important works of art.

For more information:

| Dowd, Elsbeth Linn 2011 Amphibian and Reptilian Imagery in Caddo Art. Southeastern Archaeology 30(1):79-95. Girard, Jeffrey S., Timothy K. Perttula, and Mary Beth Trubitt 2014 Caddo Connections: Cultural Interactions Within and Beyond the Caddo World. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Maryland. Harrington, Mark R. 1920 Certain Caddo Sites in Arkansas. Indian Notes and Monographs, Miscellaneous Series No. 10. Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, New York. Perttula, Timothy K., Bo Nelson, Robert L. Cast, and Bobby Gonzalez 2010 The Clements Site (41CS25): A Late 17th to Early 18th-Century Nasoni Caddo Settlement and Cemetery. Anthropological Papers No. 92. American Museum of Natural History, New York. Webb, Clarence H. 1959 The Belcher Mound, a Stratified Caddoan Site in Caddo Parish, Louisiana. Memoirs No. 16. Society for American Archaeology, Salt Lake City, Utah. |